The Pink Floyd Song Once Deemed ‘Too Sad’

Read More: The Pink Floyd Song Once Deemed ‘Too Sad’ |

After forming in 1965, Pink Floyd wasted little time expanding their creative horizons. Simply recording studio albums would not be sufficient.

Within just a few years of being a band, they turned their attention to film, composing their first score for 1968’s The Committee. The following year they did another for a film called More. Then came a production called Zabriskie Point, an American movie directed by Michelangelo Antonioni. Set in Los Angeles, it involved counter-culture protestors, policies

- Read More: The Pink Floyd Song Once Deemed ‘Too Sad’ | and California’s famous Death Valley

Music for the film was provided by a number of notable acts, including but not limited to Jerry Garci, Roy Orbison,

the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd.

For about a month, Pink Floyd lived in a luxury hotel in Rome where they began writing music, only some of which would ultimately make its way into the final film. One of those rejected songs was penned by keyboardist Richard

Richard Wright, titled “The Violent Sequence,” intended for, as its name suggests, a particularly violent portion of the film.

Wright’s original composition can be heard in the 2003 film, Pink Floyd: The Making of ‘The Dark Side of the Moon,’ in which he describes sitting in the studio, watching the aforementioned part of the film and beginning to play the chord sequence of a new song.

“At the time,” Wright said. “I think everyone thought ‘This is really good.'”

Not Good Enough for ‘Zabriskie Point’

The band thought the song was a winner,

but Antonioni thought otherwise.

“It’s beautiful,” Roger Waters recalled, mimicking the director’s Italian accent, “but is a too sad, you know? It makes me think of church.”

“He needed desperately to have control,” Nick Mason said. “So even if you did the right thing and it was perfect, he couldn’t bear to accept it because it wasn’t a choice.”

Thus, “The Violent Sequence” did not appear in Zabriskie Point, which was released in February of 1970. It promptly flopped at the box office and received widespread criticism.

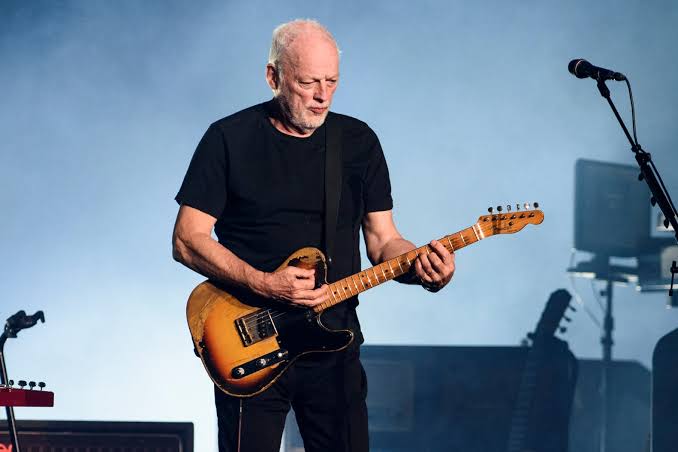

Watch Pink Floyd in Abbey Road Studios Working on ‘Us and Them’ in 1972

But as any seasoned songwriter will tell you, throwing ideas away, even rejected ones, is not advisable. “It was obviously waiting to be reborn,” David Gilmour noted.

Three years later, “The Violent Sequence” had its name changed to “Us and Them” and was the first song the band worked on in Abbey Road Studios during sessions for 1973’s The Dark Side of the Moon.

READ MORE: Underrated Pink Floyd: The Most Overlooked Song From Each Album

“Being an engineer for Pink Floyd was arguably the biggest challenge I ever gave myself,” Alan Parsons told in 2023. “They’re

sound oriented; they used the studio to the absolute maximum. So it was a big challenge as an engineer. But I think I learned a bit, and I think they learned from me as well. It was a really good team effort overall.”

The Rebirth of a Song

Clocking in at nearly eight minutes, “Us and Them” became the longest track on the album, credited to Wright and Waters, who contributed lyrics. Even if the new version didn’t sound quite as sad as Wright’s original, Waters’ words still evoked imagery of conflict, which was arguably just as rampant in 1972 as it had been in 1969.

“The first verse is about going to war, how on the front line we do’’t get much chance to

communicate with one another, because someone else has decided that we shouldn’t,” Waters explained to in 2022. “The second verse is about civil liberties, racism and color prejudice. The last verse is about passing a tramp in the street and not helping.”

“Us and Them” was also released as a single on Feb. 4, 1974, and though it didn’t chart, it still remained an integral part of The Dark Side of the Moon.

Listen to Pink Floyd’s ‘Us and Them’

Ummagumma’ (1969)

Pink Floyd wasn’t quick to discover a post-Syd Barrett direction, trying and discarding a number of musical ideas after their original frontman disappeared. Here, they settled on presenting solo material – and that only served to illustrate the concept of a sum being greater than its parts. Richard Wright offered a four-part avant-garde keyboard suite, Roger Waters endlessly dabbled with sound effects, and Nick Mason unleashed nearly nine minutes of percussive noodling. David Gilmour later admitted he “just bullshitted” through his piece. Really, they all did.More’ (1969)

‘More’ represented a turning point more than a success story for the group, as Pink Floyd took its very first steps without both Barrett and producer Norman Smith. We hear Waters begin to move to the fore as a songwriter, even as Gilmour handles all of the vocals for what would be the first of just two Pink Floyd albums (the other is our next entry, 1987’s transitional ‘Momentary Lapse of Reason’). The results, unfortunately, are more experimental than they are focused. ‘More’ simultaneously makes a rare foray into folk, even while (on the thundering ‘Ibiza Bar’) unleashing some of the band’s heaviest sounds ever.A Momentary Lapse of Reason’ (1987)

The now-departed Waters tried to sue to stop this guest-star-laden comeback album from happening, saying Pink Floyd was a “spent force creatively.” ‘Momentary Lapse of Reason,’ with its too-poppy hit single ‘Learning to Fly,’ too-draggy ‘Sorrow’ and too-familiar ‘Dogs of War,’ nearly proved it, too. But the dream-like ‘Yet Another Movie/Round and Round’ represented the best of what the remaining Floyds still had to offer, even as it provided a glimpse into the smaller successes that the reconstituted trio of Gilmour, Wright and Mason would muster for ‘The Division Bell.’Obscured By Clouds’ (1972)

This was originally conceived as a soundtrack to the French film ‘La Vallée,’ and – with its series of short, incidental pieces of music – too often plays like that, rather than as a full-fledged album effort. Still, there were important pointers to what lay ahead: ‘Free Four’ was one of the first songs in which Roger Waters dealt with the death of his father, while ‘Childhood’s End’ found David Gilmour trying his hand at lyric writing for the first time. ‘Wot’s … Uh, the Deal?’ later became part of Gilmour’s solo setlists, too.The Endless River’ (2014)

Determinedly uncommercial, ‘The Endless River’ was aimed directly at those still riveted by Pink Floyd’s often-forgotten period between the Syd Barrett years and the career-defining supernova that was ‘Dark Side of the Moon.’ This era, from 1969’s ‘More’ to 1972’s ‘Obscured by Clouds,’ saw David Gilmour’s arrival spark a wave of rangy, largely instrumental experimentation. Same with ‘The Endless River.’ Constructed from the late Richard Wright’s final recordings with the group, it revived that sense of dizzying interplay and adventure.The Final Cut’ (1983)

Originally envisioned as a soundtrack to ‘The Wall’ film, this didactic project transformed into a stand-alone effort when Waters became outraged over England’s involvement in the early-’80s Falkland Islands conflict. By this point, Wright was already out the door, and Gilmour clearly didn’t feel like fighting anymore. He had only one vocal, and a few bursts of guitar brilliance. The rest was Waters, who unleashes a series of searing diatribes on the kind of conflicts that tore his family apart – but without the magisterial musical accompaniment that used to give them flight

Leave a Reply