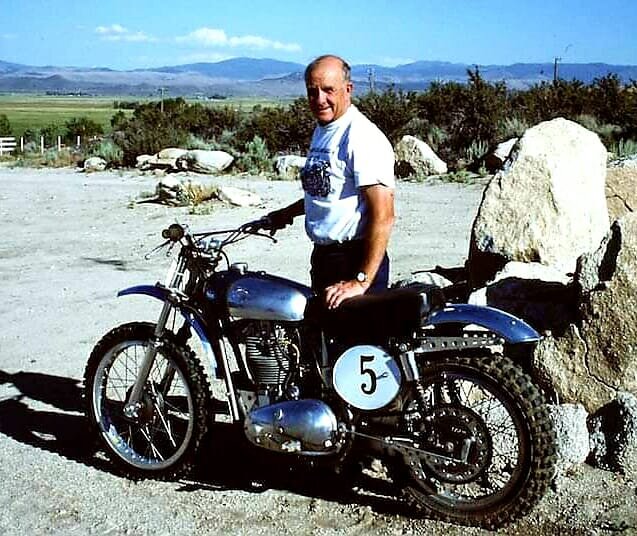

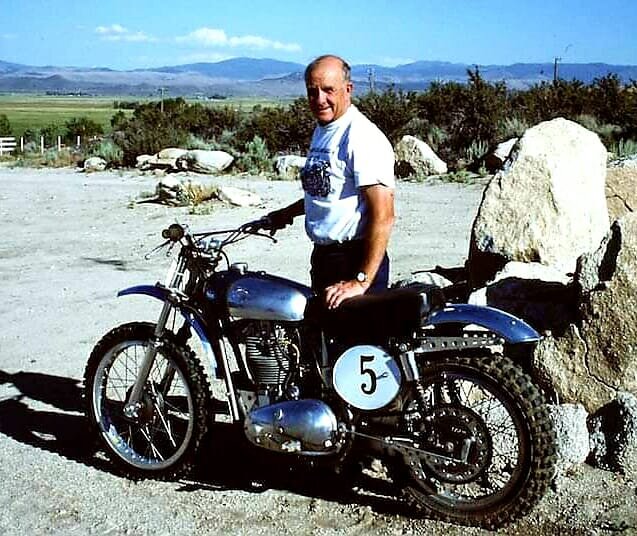

Dick Mann, two-time Daytona 200 winner and twice AMA Grand National Champion, has died aged 86.

A practical person, he learned moderation from the extremes of his mentor, the innovative but erratic Albert Gunter. Mann told me years ago about traveling and racing with Gunter: “I got a proper attitude toward racing—making a living with a motorcycle.”

Making it on your own.

Technology could open doors—Gunter and Mann showed the dirt-track paddock the value of rear suspension. Yet as Mann noted, “Albert was always working on something that was a deterrent to his career.”

Mann saw Albert “…get sucked into dynos like that whole LA bunch.”

“We never quit testing. I never had an engine on a dyno. Backroads were more in my price range.”

eople in that time concentrated on making engines pull smoothly all the way from zero throttle—listening to everything the engine was saying. At Daytona, the favored place for this was “the jungle road,” two lanes seldom patrolled by police.

Mann won his first AMA National in 1959 and was Grand National Champion twice—in 1963 and 1971. His career bridged the transition of American motorcycle racing from the gypsy life of itinerant dirt-trackers, living by their wits, to the strange professional big-time created by the explosion of motorcycle sales after 1965. Rider contracts with real money. Factory bikes. Hotel rooms.

Dick Mann was not the favored rider among those on Honda CB750-based factory bikes in the 1970 Daytona 200, but in his early years as a mechanic had developed an ear and a feel for the distress of machinery—something that a great many Americans needed back then. The Achilles’ heel of Honda’s pioneering four-cylinder in-line engine was its camshaft drive. OK at the stock peak revs of 8,500, it was becoming uncomfortable at 10,000. If there’re black rubber particles in the engine oil you drain, where’s it coming from? Something’s eating the rubber-coated cam-chain tensioners. That implied two responses: 1) fit new tensioners just before the race; 2) ride to be ahead at the finish, rather than charging to the front and trying to get away on sheer speed. That’s how it turned out.

The next year Mann was on a factory BSA Triple. “This is an 8,200-rpm engine,” the engineers told him. Privately, he decided, it sounded and felt more like 7,800.

“These Pagehiln copper-coated aluminum brake discs are the latest thing in braking,” went the crowd when discs were new. Mann chose the cast-iron rotors. Big names—Hailwood and Paul Smart—had extra performance in their engines. Once again, what that engine needed in order to win was a friend—a rider with understanding. When Mann won the Daytona 200 that second time, people were saying, “That Dick Mann sure is lucky. All those big names up front, duking it out lap after lap, but at the end, it was like he came from nowhere.

It wasn’t luck and he wasn’t nowhere. He was riding to finish. It’s not strange that Mann has been hailed for his humility. He knew how far he’d come, and from what beginnings.

Speaking of what racing has become in the MotoGP era, he said, “There are fantastically talented kids now (entering racing). I don’t think they could have made it in our day. And we couldn’t have made it in these days. Things were just different.”

Leave a Reply